continues Paradoxes and Logic (part 1)

“Draw a Distinction”

Spencer-Brown introduces the elementary building block of his formal logic with the words ‘Draw a Distinction’. Figure 1 shows this very simple formal element:

Fig 1: The form of Spencer-Brown

A Radical Abstraction

In fact, his logic consists exclusively of this building block. Spencer-Brown has thus achieved an extreme abstraction that is more abstract than anything mathematicians and logicians have found so far.

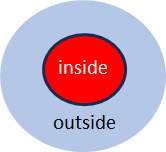

What is the meaning of this form? Spencer-Brown is aiming at an elementary process, namely the ‘drawing of a distinction’. This elementary process now divides the world into two parts, namely the part that lies within the distinction and the part outside.

Fig. 2: Visualisation of the distinction

Figure 2 shows what the formal element of Fig. 1 represents: a division of the world into what is separated (inside) and everything else (outside). The angle of Fig. 1 thus becomes mentally a circle that encloses everything that is distinguished from the rest: ‘draw a distinction’.

The angular shape in Fig. 1 therefore refers to the circle in Fig. 2, which encompasses everything that is recognised by the distinction in question.

Perfect Continence

But why does Spencer-Brown draw his elementary building block as an open angle and not as a closed circle, even though he is referring to the closedness by explicitly saying: ‘Distinction is perfect continence’, i.e. he assigns a perfect inclusion to the distinction. The fact that he nevertheless shows the continence as an open angle will become clear later, and will reveal itself to be one of Spencer-Brown’s ingenious decisions. ↝ imaginary logic value, to be discussed later.

Marked and Unmarked

In addition, it is possible to name the inside and the outside as the marked (m = marked) and the unmarked (u = unmarked) space and use these designations later in larger and more complex combinations of distinctions.

Fig. 3: Marked (m) and unmarked (u) space

Fig. 3: Marked (m) and unmarked (u) space

Distinctions combined

To use the building block in larger logic statements, it can now be put together in various ways.

Fig. 4: Three combined forms of differentiation

Figure 4 shows how distinctions can be combined in two ways. Either as an enumeration (serial) or as a stacking, by placing further distinctions on top of prior distinctions. Spencer-Brown works with these combinations and, being a genuine mathematician, derives his conclusions and proofs from a few axioms and canons. In this way, he builds up his own formal mathematical and logical system of rules. Its derivations and proofs need not be of urgent interest to us here, but they show how carefully and with what mathematical meticulousness Spencer-Brown develops his formalism.

Re-Entry

The re-entry is now what leads us to the paradox. It is indeed the case that Spencer-Brown’s formalism makes it possible to draw the formalism of real paradoxes, such as the barber’s paradox, in a very simple way. The re-entry acts like a shining gemstone (sorry for the poetic expression), which takes on a wholly special function in logical networks, namely the linking of two logical levels, a basic level and its meta level.

The trick here is that the same distinction is made on both levels. That it involves the same distinction, but on two levels, and that this one distinction refers to itself, from one level to the other, from the meta-level to the basic level. This is the form of paradox.

Exemple Barber Paradox

We can now notate the Barber paradox using Spencer-Brown’s form:

Fig. 5: Distinction of the men in the village who shave themselves (S) or do not shave themselves (N)

Fig. 6: Notation of Fig. 5 as perfect continence

Fig. 5 and Fig. 6 show the same operation, namely the distinction between the men in the village who shave themselves and those who do not.

So how does the barber fit in? Let’s assume he has just got up and is still unshaven. Then he belongs to the inside of the distinction, i.e. to the group of unshaven men N. No problem for him, he shaves quickly, has breakfast and then goes to work. Now he belongs to the men S who shave themselves, so he no longer has to shave. The problem only arises the next morning. Now he’s one of those men who shave themselves – so he doesn’t have to shave. Unshaven as he is now, however, he is a men he has to shave. But as soon as he shaves himself, he belongs to the group of self-shavers, so he doesn’t have to be shaven. In this manner, the barber switches from one group (S) to the other (N) and back. A typical oscillation occurs in the barber’s paradox – and in all other real paradoxes, which all oscillate.

How does the Paradox Arise?

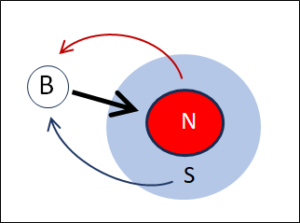

Fig. 7: The barber (B) shaves all men who do not shave themselves (N)

Fig. 7, shows the distinction between the men N (red) and S (blue). This is the base level. Now the barber (B) enters. On a logical meta-level, it is stated that he shaves the men N, symbolised by the arrow in Fig. 7.

The paradox arises between the basic and meta level. Namely, when the question is asked whether the barber, who is also a man of the village, belongs to the set N or the set S. In other words:

→ Is B an N or an S ?

The answer to this question oscillates. If B is an N, then he shaves himself (Fig. 7). This makes him an S, so he does not shave himself. As a result of this second cognition, he becomes an N and has to shave himself. Shaving or not shaving? This is the paradox and its oscillation.

How is it created? By linking the two levels. The barber is an element of the meta-level (macro level), but at the same time an element of the base level (micro level). Barber B is an acting subject on the meta-level, but an object on the basic level. The two levels are linked by a single distinction, but B is once the subject and sees the distinction from the outside, but at the same time he is also on the base level and there he is an object of this distinction and thus labelled as N or S. Which is true? This is the oscillation, caused by the re-entry.

The re-entry is the logical core of all true paradoxes. Spencer-Brown’s achievement lies in the fact that he presents this logical form in a radically simple way and abstracts it formally to its minimal essence.

The paradox is reduced to a single distinction that is read on two levels, firstly fundamentally (B is N or S) and then as a re-entry when considering whether B shaves himself.

The paradox is created by the re-entry in addition to a negation: he shaves the men who do not shave themselves. Re-entry and negation are mandatory in order to generate a true paradox. They can be found in all genuine paradoxes, in the barber paradox, the liar paradox, the Russell paradox, etc.

Georg Spencer-Brown’s achievement is that he has reduced the paradox to its essential formal core:

→ A (single) distinction with a re-entry and a negation.

His discoveries of distinction and re-entry have far-reaching consequences with regard to logic, and far beyond.

Let’s continue the investigation, see: Form (Distinction) and Bit

Translateion: Juan Utzinger