Information reduction is everywhere

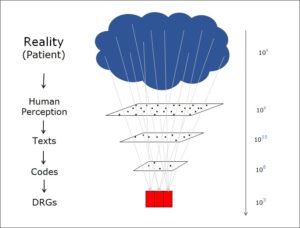

In a previous post, I described how the coding of medical facts – a process that leads from a real-world situation to a flat rate per case (DRG) – involves a dramatic reduction in the amount of information:

Information reduction

This information reduction is a very general phenomenon and by no means limited to information and its coding in the field of medicine. Whenever we notice something, our sensory organs – for example our retinas – reduce the amount of information we take in. Our brain then simplifies the data further so that only the essence of the impressions, the part that is important to us, arrives in our consciousness.

Information reduction is necessary

If you ask someone how much they want to know, most people will tell you that they want to know as much as possible. Fortunately, this wish is not granted. Many will have heard of the savant who, after flying over a city just once, was able to draw every single house correctly from memory. Sadly, the same individual was incapable of navigating his everyday life unaided – the flood of information got in the way. So knowing every last detail is definitely not something to aspire to.

Information reduction means selection

If it is necessary and desirable to lose data, the next question concerns which data we should lose and which we should retain. Some will imagine that this is a natural choice, with the object we are looking at determining which data is important and which is not. In my opinion, this assumption is simply wrong. It is the observer who decides which information is important to him and which he can disregard. The information he chooses to retain will depend upon his goals.

Of course, the observer cannot get information out of the object that the object does not contain. But the decision as to which information he considers important is down to him – or to the system he feels an allegiance to.

This is particularly true in the field of medicine. What is important is the information about the patient that allows the doctor to make a meaningful diagnosis – and the system of diagnoses depends essentially on what can be treated and how. Medical progress means that the aspects and data that come into play will change over time.

In other words, we cannot know everything, and we must actively reduce the amount of information available so that we can make decisions and act. Information reduction is inevitable and always involves making a choice.

Different selections are possible

Which information is lost and which is retained? The answer to this question determines what we see when we look at an object.

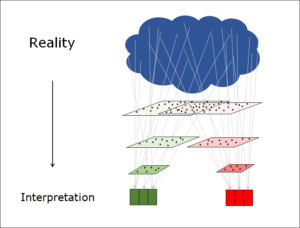

Various information selections (interpretations) are possible

Because the observer – or the system that he lives in and that moulds and shapes his thinking – decides which information to keep, different selections are possible. Depending on which features we prioritise, different individual cases may be placed in a given group or category and different viewers will thus arrive at different interpretations of the same reality.

This is a page about information reduction — see also overview.

Translation: Tony Häfliger and Vivien Blandford