Initial wish: changing the fundamental tone during a piece of music

In the preceding post, we saw that the just intonation is not pure any more when the fundamental tone is changed since certain intervals change. The further removed the key, the more tones fail to accord with the calculated, i.e. resonant tones.

If the frequencies of the scale tones are very slightly shifted – i.e. tempered – then we can also change over into neighbouring keys, i.e. we can modulate. In the equal temperament, we can actually change over to any fundamental tone whatever, and this temperament has successfully prevailed in Europe since the Baroque.

How the equal temperament works

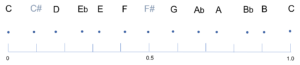

In Fig. 1, you can see the resonant, i.e. pure intervals between a fundamental tone and its octave.

Fig. 1: Resonant intervals above the fundamental tone C in a logarithmical representation

In the above figure, I also included the indirectly resonant tones C# and F#, thus closing the gaps in the band of the most resonant intervals. What is conspicuous in Figure 1 is the fact that the twelve tones are not regularly, but almost equally distributed across the octave. Could this be exploited musically?

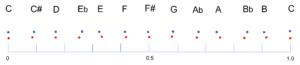

Fig. 2: Pure (blue) and equal (red) distribution of the 12 scale tones

Figure 2 shows the comparison between a natural, i.e. pure distribution of scale tones with a completely equal distribution. As you can see, the displacements are visible, but not all that big. The irregular, pure tones are slightly shifted, which results in a completely equal distribution of the tones. This slightly changed, but now equal distribution is called the equal temperament.

Since the distances between the twelve tones are precisely equal, it does not matter on which fundamental tone we establish the musical scales:

C major: C – D – E – F – G – A – B – C

E-flat minor: Eb – F – G – Ab – Bb – C – D – Eb

As you can easily check, the relative distances between the individual tones are now precisely equal in the tempered frequencies, no matter whether in C major, E-flat major or any other key.

The equal temperament is a radical solution and as such the end of a historical development that underwent several interim solutions (such as the Werckmeister temperament and many more). This historical development and the details of the practical configuration are extensively documented in the internet and the literature and are easy to find. What interests us here, however, are two completely different questions:

- Why does tempering work although we do not have any precise fractions for the resonances any longer?

- What are the compositional consequences?

More about this in the following posts.

This is a post about the theory of the three worlds.