Information reduction in thermodynamics

A very specific example of information reduction can be found in the field of thermodynamics. What makes this example so special is its simplicity. It clearly illustrates the basic structure of information reduction without the complexity found in other examples, such as those from biology. And it’s a subject many of us will already be familiar with from our physics lessons at school.

What is temperature?

A glass of water contains a huge amount of water molecules, all moving at different speeds and in different directions. These continuously collide with other water molecules, and their speed and direction of travel changes with each impact. In other words, the glass of water is a typical example of a real object that contains more information than an external observer can possibly deal with.

A glass of water contains a huge amount of water molecules, all moving at different speeds and in different directions. These continuously collide with other water molecules, and their speed and direction of travel changes with each impact. In other words, the glass of water is a typical example of a real object that contains more information than an external observer can possibly deal with.

That’s the situation for the water molecules. So what is the temperature of the water in the glass?

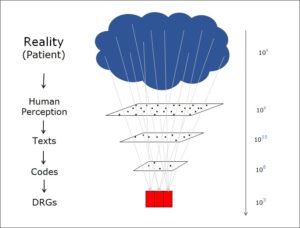

As Ludwig Boltzmann was able to demonstrate, temperature is simply the result of the movement of the many individual water molecules in the glass. The faster they move, the more energy they have and the higher is the temperature of the water As Ludwig Boltzmann explained, the temperature of the water in the glass can be calculated statistically from the kinetic energy of the many molecules. Billions of molecules with their constantly changing motion produce exactly one temperature. Thus, a large amount of information is converted into a single fact.

The micro level and the macro level

It’s worth noting that the concept of temperature cannot be applied to individual molecules. At this level, there is only the movement of many single molecules, which changes with each impact. The kinetic energy of the molecules depends on their speed and thus changes with each impact.

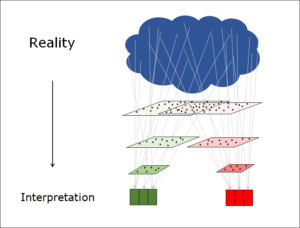

Although the motion of the water molecules is constantly changing at the micro level, the temperature at the macro level of the glass of water remains comparatively constant. And, in the event that it does change, for example because heat is given off from the water at the walls of the glass, there are formulas that can be used to calculate the movement of the heat and thus the change in temperature. These formulas remain at the macro level, i.e. they do not involve the many complicated impacts and movements of the water molecules.

The temperature profile can thus be described and calculated entirely at the macro level without needing to know the details of the micro level and its vast number of water molecules. Although the temperature (macro level) is defined entirely and exclusively by the movement of the molecules (micro level), we don’t need to know the details to predict its value. The details of the micro level seem to disappear at the macro level. This is a typical case of information reduction.

In the next post I’ll make some precisions concerning the waterglass.

This is a page about information reduction — see also overview.

Translation: Tony Häfliger and Vivien Blandford