In a preceding post we saw that in rule-based AI, intelligence is situated in the rules. These rules are drawn up by people, and the system is as intelligent as the people who have formulated them. Where, then, is intelligence situated in corpus-based AI?

The answer is somewhat more complicated than in the case of rule-based systems. Let us therefore have a closer look at the structure of such a corpus-based system. It is established in three steps:

- compiling as large a data collection as possible (corpus),

- assessing this data collection,

- training the neural network.

The network can be applied as soon as it has been established:

- applying the neural network.

Let’s have a closer look at the four steps.

Step 1: Compiling the data collection

In our tank example, the corpus (data collection) consists of photographs of tanks. Images are typical of corpus-based intelligence, but the collection may of course also contain other kinds of information such as customers’ queries submitted to search engines or GPS data from mobile phones. The typical feature is that the data of each singular entry are made up of so many individual elements (e.g. pixels) that their evaluation by rules consciously drawn up by people becomes too labour-intensive. In such cases, rule-based systems are not worthwhile.

A collection of data alone, however, is not enough. The data now have to be assessed.

Step 2: Assessing the corpus

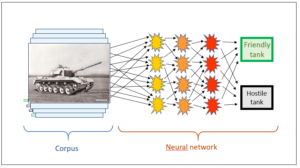

Fig. 1 displays the familiar picture of our tank example. On the left-hand side, you can see the corpus. In this figure, it has already been assessed; the assessment is symbolised by the black and green flags on the left of each tank image.

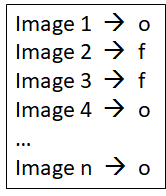

In simplified terms, the assessed corpus can be imagined as a two-columned table. The left-hand column contains the information about the images, the right-hand column contains the assessment, and the arrow between them is the categorisation, which thus becomes an essential part of the corpus in that it states to which category (o or f) each individual image belongs, i.e. how it has been assessed.

Typically, the volumes of information in the two columns differ greatly in size. Whereas the assessment in the right-hand column of our tank example consists of precisely one bit, the image in the left-hand column contains all the pixels of the photograph; each and every pixel’s position, colour, etc. have been stored – i.e. a rather large data volume. This difference in the size ratio is typical of corpus-based systems – and if you have philosophical interests, I would like to point out its nexus with the issue of information reduction and entropy (cf. posts on information reduction). At the moment, however, the focus is on intelligence in corpus-based AI systems, and we note that in the corpus, every image is allocated its correct target category.

We do not know how this categorisation happens, for it is carried out by human beings with the neurons in their own heads. These human beings are unlikely to be conscious of the precise behaviour of their neurons, and thus could not identify the rules by which this process is governed. They do know, however, what the images represent, and they indicate this in the corpus by assigning them to the relevant categories. This categorisation is introduced into the corpus from the outside by human beings; it is one hundred per cent man-made. At the same time, this assessment is an absolute condition and the basis for the establishment of the neural network. Later, too, when the completely trained neural network no longer requires the corpus with the categorisations that were brought in from the outside, it will still have been necessary for the network to be set up to be able to work at all.

Where, then, does this intelligence come from in the assignment to the categories o) and f)? It is ultimately human beings who carry out this categorisation (and may also fail to do it correctly); it is their intelligence. Once the categorisation in the corpus has been noted, this is not active intelligence any longer, but fixed knowledge.

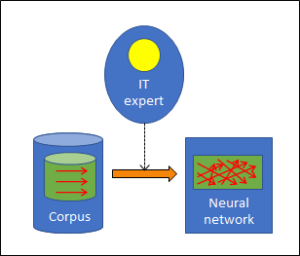

The assessment of the corpus is a crucial stage, for which intelligence is undoubtedly required. The compiled data collection has to be assessed, and the domain expert who carries out this assessment has to guarantee that it is correct. In Fig. 2, the domain expert’s intelligence is represented by the yellow sphere. The corpus receives the knowledge thus generated through the categorisations, which in turn are represented as red arrows in Fig. 2.

Knowledge is something different from intelligence. In a certain sense, it is passive. In this sense, the pieces of information contained in the corpus are objects of knowledge, i.e. categorisations which have been formulated and need not be processed any longer. Conversely, intelligence is an active principle which is capable of making valuations on its own as is done by the human expert. The elements in the corpus, however, are data or – in the case of the above-mentioned results of the experts’ intelligence – permanently formulated knowledge.

To distinguish this knowledge from intelligence, I did not colour it yellow in Fig 2, but green.

Thus we usefully distinguish between three things:

– data (the data collection in the corpus),

– knowledge (the completed assessment of these data),

– intelligence (the ability to carry out this assessment).

Step 3: Learning stage

At the learning stage, the neural network is established on the basis of the learning corpus. The success of this process again requires a considerable degree of intelligence; this time, it comes from AI experts, who enable the learning stage to work and who control it. A crucial role is played by algorithms here: they are responsible for the correct evaluation of the knowledge in the corpus and for the neural network taking precisely that shape which will ensure that all the categorisations contained in the corpus can be reproduced by the network itself.

The extraction of knowledge and the algorithms used in the process are symbolised by the brown arrow between corpus and network. The algorithms may appear to display a certain degree of intelligence even though they do not do anything that has not been predefined by the IT experts and the knowledge in the corpus. The emerging neural network itself does not have any intelligence of its own but is the result of this process and thus of the experts’ intelligence. It contains a substantial amount of knowledge, however, and is therefore coloured green in Fig. 3, like the knowledge in Fig. 2. In contrast to the corpus, however, the categorisations (red arrows) are significantly more complex, in precisely the way in which neural networks work in a more complex manner than a simple two-columned table does (Tab. 1).

There is something else that distinguishes the knowledge in the network from the corpus: the corpus contains knowledge about individual cases whereas the network is abstract. It can therefore also be applied to cases that have been unknown to date.

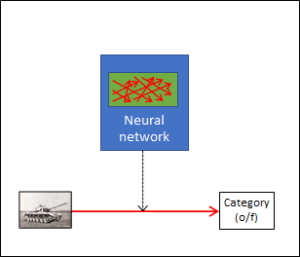

Step 4: Application

In Fig. 4, a previously unknown image is assessed by the neural network and categorised according to the knowledge stored in the network. This does not require a corpus any longer, nor does it require an expert; the “trained” but now fixed wiring in the neural network is enough. At this moment, the network is no longer capable of learning anything new. However, it is able to attain perfectly impressive achievements with a completely new input. This performance has been enabled by the preceding work, i.e. the establishment of the corpus, the (hopefully) correct assessments and the algorithms of the learning stage. Behind the learning corpus, there is the domain experts’ human intelligence; behind the algorithms of the learning stage, there is the IT experts’ human intelligence.

Conclusion

What appears to be artificial intelligence to us is the result of the perfectly human, i.e. natural intelligence of domain experts and IT experts.

In the next post, we will have an even closer look at what kind of knowledge a corpus really contains, and at what AI can get out of the corpus and at what it can’t.

This is a post about artificial intelligence.

Translation: Tony Häfliger and Vivien Blandford